What we are witnessing is a luku hoʻopau. A willful slaughter. Here are the numbers: It has been almost eight months and over 35,000 Palestinians have been killed. Even with the UN’s revised numbers, over half of them are women and children. It is estimated that at least 180 people a day are killed in Gaza. 1.9 million people have been displaced, and over 60 percent of Gaza has been destroyed. 37.5 million tons of rubble cover Gaza, which will take at least 14 years to clear. 7,500 metric tons of unexploded ordnance still litter the Gaza Strip. Tens of thousands of Palestinians are forced to subsist on 245 calories per day.

These are just some of the numbers related to the genocide that is taking place in Palestine. These numbers are probably already outdated. Too low. Tomorrow they will be higher. Next week they will continue to swell. Imagine next month. It has already been almost eight months. Eight months, and these numbers are not enough to convince some of our lāhui to care. To stand with the oppressed. To think about what we consider pono. Some of us are too invested in the colonial-authored narratives about Palestine to change their minds. Some of us have the thinnest excuses to justify our indifference to this luku hoʻopau. Those people are not going to read this post. They will just give their opinions in the comments no matter what we say. But we are hopeful that there are some of us out there who are just not sure, who have doubts, who may be looking for a reason to change their minds, who have space in their naʻau for what we are trying to say.

So we are going to move away from numbers and appeal to you as a kanaka, a person. And to be a kanaka means to be in pilina, in a network of relationship and connection that binds us to the land and binds us to others, makes them responsible for us and us responsible for them. In terms of responsibility though, truthfully, it is easier to set our sights closer to home, focus on the people we see every day. We have so many issues that we as a lāhui are dealing with at home in Hawaiʻi: houselessness, rising poverty and cost of living, militarization, insufficient education, struggles to protect our land. Furthermore, it is easier still to ignore even these issues. It is hard enough to mālama our ʻohana, much less anything or anyone beyond that. And yet our kūpuna have left for us a myriad of examples showing how capacious our aloha is, how deep our naʻau are. Perhaps as with so many things in our lives, that means we can turn to our kūpuna here as well.

He mana ʻoliva.

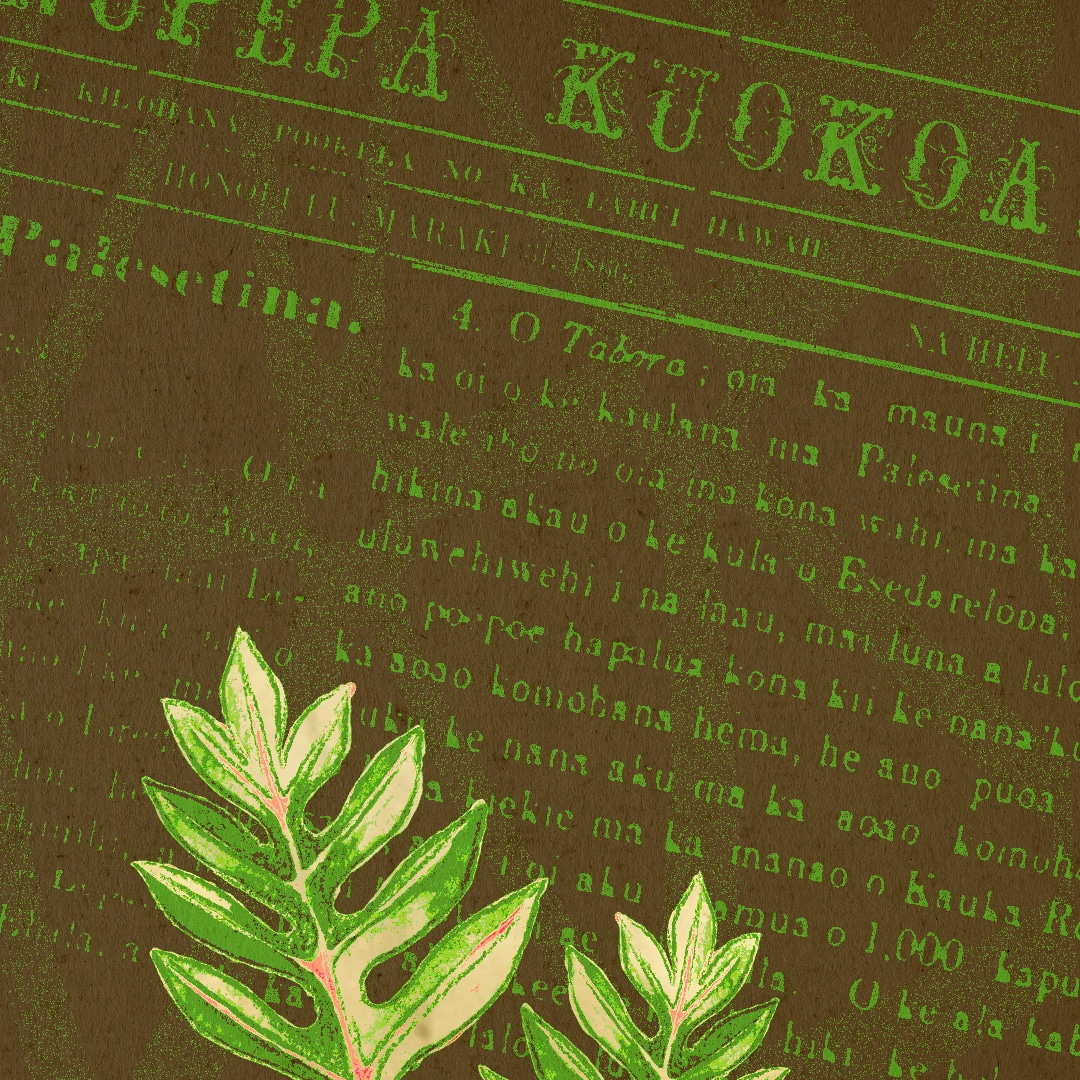

Even in the midst of the tumultuous domestic situation of the nineteenth century, like the Paulet affair, the Bayonet Constitution, the overthrow and more, our people never stopped paying attention to what was happening elsewhere. Sometimes we looked abroad for solutions, but it was often just because of that capacious aloha. The lāhui is/was curious and loving. Aliʻi kept up correspondence with heads of state, intellectuals, and artists around the world, and Hawaiian-language newspaper editors would even row out to ships in order to get the latest news and newspapers from abroad to meet the voracious appetite our people had for what was going on. The lāhui kept up with news of things like the Cuban war of independence, Michael Collins and the struggles of the Irish, and yes, even though it was at the tail end of the Hawaiian-language newspaper era, they paid attention to what was going on in Palestine as well.

This acknowledgment of our pilina with others around the world was evidenced through things like the legations the Hawaiian kingdom had in dozens of countries, kānaka going off to fight in the US civil war, the lāhui collecting money for places hit hard by natural disasters, and even through legislation. One example is how the Hawaiian kingdom outlawed slavery a decade before the United States did. It is easy to brush this off as mere historical trivia. We did not have chattel slavery here, and it was not woven through the fabric of Hawaiʻi’s economy the way it was with the United States, so it could be seen as not that big a deal to abolish it. So why did our kūpuna do it? The first part of that answer is that they were trying to create a society that explicitly centered pilina and cared for all, standing as a model for others around the world. The second part of the answer is that not only did our kūpuna abolish slavery, they dictated that any enslaved person who ended up in Hawaiʻi would be considered free. It is not clear from the historical record how many enslaved people made it to Hawaiʻi and gained their freedom, but it is likely that this stipulation and Hawaiʻi’s status as a major port played some part in disrupting the blackbird/slavery trade in the Pacific.

Our kūpuna also acknowledged that true solidarity with other colonized peoples was a way forward for us. An example of this is when Kalākaua tried to form a Polynesian Confederacy with Sāmoa, Tonga, and other Pacific nations, sending John Bush, one of the leading intellectuals and aloha ʻāina of the times, on the ship Kaʻimiloa to pursue this goal. Kalākaua recognized that strengthening our pilina with other people fighting colonialism was a path to liberation for us all. Once the Bayonet Constitution was implemented in 1887, plans for the confederacy were cut off. Though mainly ignored by Western historians or ridiculed as showing the ineptness of Kānaka in navigating politics, the threat this confederacy posed to colonial powers was real, evidenced by how quickly it was shut down in 1887.

Kalākaua’s Hawaiian Youths Abroad program was also shut down in 1887, the idea of Kānaka learning art, law, military tactics, Western medicine, trades, and more in England, Japan, China, Italy, and the United States to benefit the lāhui Hawaiʻi also being too threatening for the foreign elite. We are at our most powerful and adversarial to the structures of colonialism when we are connected and grounded in our pilina, learning what we can from whom we can and using that ʻike to serve Hawaiian purposes. Kalākaua knew this (check out the history of the Hale Nauā too) but he was characterized by his contemporary critics and outsider-authored histories as a debauched profligate only concerned with his image.

And this is where the crux of the problem lies in regards to solidarity with other Indigenous peoples, other oppressed peoples, just other people, and that is the way that the stories about us are told. Colonialism 101 is to shape the narrative, the history, the story to dehumanize us, to characterize us as incapable, and to justify our oppression. To make us think that we are utterly unique, and thus absolutely alone, in our struggles.

Our kūpuna recognized the power of stories, as each version of a moʻolelo was called a mana. As most of us know, mana is a kind of power that can be imbued in people, places, ideas, and more. So each time a particular story is retold, it gets more and more mana.

One of the important things that should clue us as Kānaka into the fact that something underhanded (or lima koko, bloody-handed) is going on is that the kinds of stories told about Palestinians—in the media, from the pulpit, in political speeches, on social media—are so similar to the kinds of stories we have heard being told about us. The contexts are different as are the specific goals and the contemporary situations that these narratives have led us to, but the language used and the overarching purposes are so similar. If the colonial story ain’t broke, don’t fix it: We are violent, bloodthirsty savages. Uneducated, inferior, inhuman. “Human animals.”

When the missionaries arrived here in Hawaiʻi in 1820, they were horrified and questioned if Hawaiians were even human. They had just spent several months with a handful of highly educated Hawaiian youth as they traveled here aboard the Thaddeus but the stories that they had been told about the poor and spiritually destitute Hawaiians held more sway in their hearts than the evidence of their eyes. These contradictions defy logic until you remember that the missionaries had come to “save” us savages, which would have been quite difficult had they acknowledged that what had greeted them on arrival was not a culture in need of saving but actually a vibrant culture that had learned over hundreds of generations to connect with the ʻāina and kai in ways that were unmatched.

Pilina. Pono. Kū‘oko‘a

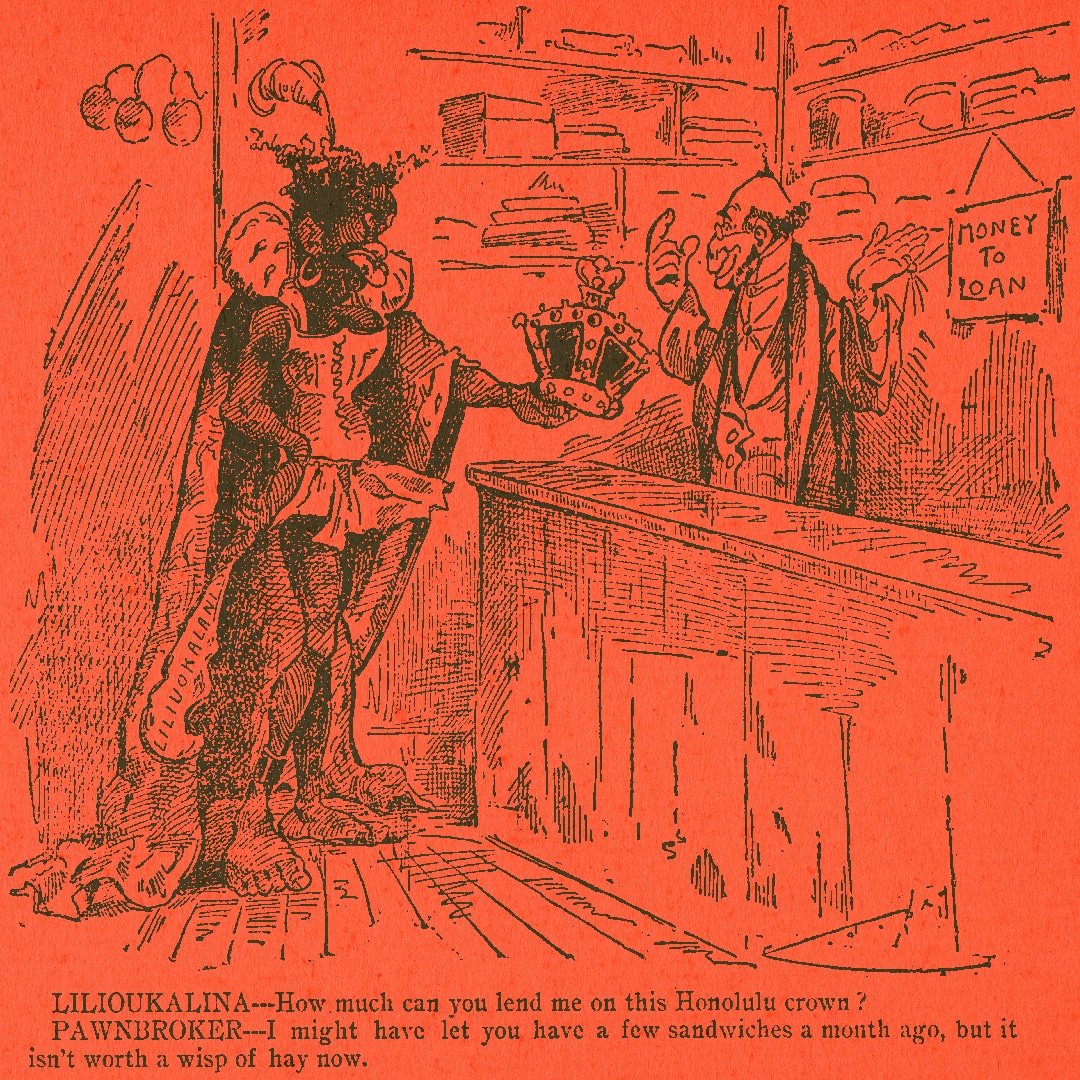

Another mana of this story was that we were backwards and unable to govern ourselves, a narrative that was used to justify all sorts of political machinations and attempts to seize our ʻāina including the Bayonet Constitution and the overthrow. Just look at the caricatures of Liliʻuokalani from the time. In the eyes of the people giving mana to these narratives, she was doubly guilty: she was not just a savage, but a woman as well. The more we resisted oppression and colonialism by using introduced ideas and technologies in ways that served Hawaiian aims, the more we were painted as savages. This continued narrative of Hawaiians as inhuman and savage led to the killing of Joseph Kahahawai in 1932 by Navy Lieutenant Thomas Massie and others after the false accusations of the Massie trial were unsuccessful. And if you think that no one tells those kinds of stories about Kānaka anymore, which story do you think had mana in 2011 at a Waikīkī McDonald’s? Which narrative was driving the claims in 2019 that kiaʻi protecting the Mauna were violent and that the Puʻuhonua was filled with drinking, drugs, and crime? What story was running in the head of the astronomy professor who not just believed, but passed on, the story that the Kānaka Maoli who graduated from the Kamehameha Schools were not only not intelligent, but sometimes did not even know how to read?

If we can so quickly recognize the absolute falsity of these narratives about us as Kānaka Maoli and discern what the end goals of these kinds of stories are, what do you think we find in the stories told about Palestinians? What kinds of affinities will we find in these moʻolelo? Our moʻolelo document our displacement from ʻāina through economics, politics, and militarism. Their moʻolelo speak of the Nakba, or Catastrophe, in which 750,000 Palestinians were expelled from their homes in 1948. There are around 1,000,000 people living on Oʻahu now, so if this had taken place in our moʻolelo, nearly 8 out of 10 people on this island would have been made to leave. For the people of Palesetina, over 500 of their villages and cities were destroyed and between 8,000 and 15,000 men, women, and children killed, with documented cases of rape and terrorist tactics including car bombs being used against civilians in a series of over 70 massacres. Another version of that story was retold in 1967.

Our stories talk about the pain of our ʻāina being destroyed and injured in places like Kahoʻolawe, Mākua, Waikāne, and Pōhakuloa. Their stories talk about how hundreds of thousands of homes in Gaza have been destroyed as well as thousands of mosques, churches, restaurants, colleges, and other buildings, and how 7,500 metric tons of unexploded ordnance remain.

How Queen Lili‘uokalani was characterized in colonial controlled storytelling in the 1890s.

Our moʻolelo proudly tell the ways we have fought for our ea, for our sovereignty, for our ʻāina, for our lāhui. They tell of how many times the colonial forces we have been fighting against change the rules, move the goalposts, ignore their own laws, ignore international law. And yes, Palestinian stories include armed protest (just as ours did in 1889 and 1895), but their stories also show that they have pursued every available avenue of kūʻē, from peaceful protests, political lobbying, and financial boycotting (BDS), all of which have been met with mass violence and further strictures placed upon them as a people. The United States has tried to make boycotts in support of Palestine illegal. The overwhelmingly peaceful March of Return in 2018 was met with tanks, artillery fire, and bullets. 214 Palestinians were killed, and 36,100 were injured, compared to one Israeli soldier who died and 7 who were injured.

And our stories, both traditional and contemporary, feature the pain of population collapse. Introduced diseases, rather than violence, wiped out the vast majority of our kūpuna, across all branches of our society. No family, no lineage, no cultural practice escaped unscathed. Today we are a thriving people full of abundance celebrating the richness of what we have retained and what we continue to create, but we have not yet even been able to fully grasp the scale of what was lost. For Palestinians, that story is still going on. Who knows how long it will take their lāhui to heal from this? We have yet to recover, and it has been over 200 years.

The scale of what is happening is different, the structures of oppression and even the sheer amounts of oppression and violence visited upon them are different, the historical circumstances that lead to the current historical moment are different. But these differences are not insurmountable. These moʻolelo should guide where our aloha should go. What is really at stake here? Who are the true perpetrators of systemic violence? Who is actually facing extinction as a people? Can we mourn the hundreds of innocents killed by Hamas while still asserting that killing tens of thousands of Palestinians is no way to even out the inhuman balance sheet? The pilina in the moʻolelo we share gives us answers. Is the situation and history more complicated than we have space, time, and even ʻike to present here? Of course. But does the narrative of “It’s complicated” also serve to cover inaction in the face of genocide? Yes. It is complicated, but it really comes down to what moʻolelo we want to have as part of our moʻokūʻauhau, what we give our mana to, what story we want to pass down through our lineage. Is the story we tell our keiki and moʻopuna going to be that we learned the moʻolelo of our kūpuna and the lesson we took from them is to stand up for ourselves and no one else? To look away when an entire people are being luku wale ʻia? Or is the story going to be that we are a people of pono, principle, and pilina who stand up against oppression where we find it because it is a kuleana we have inherited for generations? We know what kind of story we have been telling here at Kanaeokana, but as for the story you would like to tell, it’s up to you. You have to decide what your story is going to be. You have the mana now.

“From ‘ulu to olive tree.”

Explore more: waihona.net