E Ala Mai:

Awakening Ea in a Militarized Hawai‘i

E Ala Mai:

Awakening Ea in a Militarized Hawai‘i

What We Lose When We Forget

In the pre-dawn darkness of a Hawaiʻi morning, the silence is broken not by the call of native birds returning to roost, but by the mechanical whoop-whoop-whoop of military helicopters cutting through hushed valleys. This is the reality of life under occupation, where the rhythms of ʻāina are drowned out by the cadence of empire, where the breath of ea1 struggles beneath the suffocating weight of military dominance. When the rolling thunder of tanks wrests away the ea of the earth, depleted uranium lingers for millennia in the soil, and jet fuel seeps into freshwater supplies, empire does more than occupy ʻāina, it spills into every aspect of life: economy, housing, language, water, memory, and so much more.

For over a century, the United States military has colonized our consciousness, reshaped our economy around dependency, and taught our people to mistake subjugation for security. But occupation is never just physical. It distorts the stories we’re told about ourselves, the futures we’re allowed to imagine, and the relationships we’re able to form with ʻāina and with each other. This is the deeper violence of militarism2 in Hawaiʻi, not just the visible harms and life threatening injustices like poisoned water and stolen ʻāina, but the quiet erosion of our ability to envision ourselves as a sovereign people, capable of shaping our own destiny, for today and for generations to come.

Even now, when we dare to question that dependence, we’re often met with false choices. Shallow statements like “better the United States than China” suggest that our only options are submission or substitution, as if Hawaiʻi’s highest aspiration is to choose between competing empires. This is how the colonization of mindsets works. It limits our future to what empire allows and erases the truth that our people housed, fed, governed, and engaged in diplomacy long before western warships entered our harbors. We were never destined to be taken, only interrupted on the path to our destiny.

Reclaiming ea—our life, breath, and sovereignty—means rejecting the narratives that equate militarism with safety and imperial control with inevitability.

Military Spending and Its Impact on Hawai‘i

In recent years, direct DoD spending accounted for 8.3% of Hawai’i’s GDP3, the second highest share compared to U.S. states. It represents the second-largest sector of Hawaiʻi’s economy. In 2022, federal defense spending in Hawaiʻi was over four times higher than the U.S. average of 2.2% seen in the states. These funds support an estimated 68,750 jobs.

But this isn’t a reflection of generosity or genuine investment in Hawaiʻi’s economy and people. It’s a reflection of the military’s outsized presence and Hawaiʻi’s central role in advancing U.S. and allied dominance in the Pacific. The economic imprint is not benign, it is the material foundation of an occupation. Behind the spreadsheets and subsidies lies a deeper cost: our land, our compliance, and our silence.

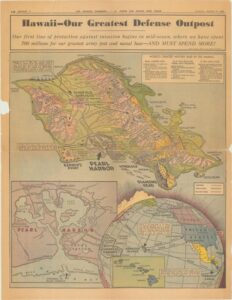

In their eyes we are a strategic outpost, a launchpad for rapid deployment, intelligence gathering, and power projection across the Pacific. According to the Military and Community Relations Office, Hawaiʻi “enables rapid deployment, intelligence gathering, and coordination with allies… making [it] a cornerstone of U.S. and allied defense strategy.” These statements don’t describe protection. They describe utility. From their own words and actions, Hawaiʻi is not treated as part of an American nation in the way “national defense” might imply. Again, they see and treat our islands as a mere staging place from which the U.S. exerts its defense of its North American homeland and its offensive plans to maintain dominance throughout the Pacific arena.

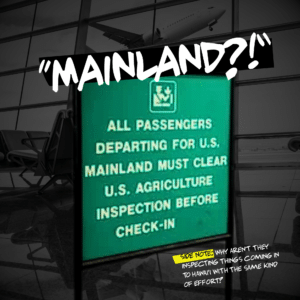

Even our everyday language betrays this worldview. The term “mainland,” still used on airport signage and in common speech, reinforces the idea that Hawaiʻi is peripheral and subordinate—never the center, always the colony. It normalizes the idea that our highest function is to serve the needs of another nation.

In this light, the military’s economic presence is not for Hawaiʻi—it is over Hawaiʻi. It secures control, access, and global reach, while expecting our gratitude in return. But gratitude is difficult to muster when the price of that presence includes the daily risks of contamination, cultural erasure, and the looming threat of conflict. This is why experiences such as the 2018 false missile alert felt not just probable but real.

Housing Pressure and the Military Footprint

Militarism does not just operate at the level of policy and geopolitics. It dictates who gets to stay in our homeland, and who must leave.

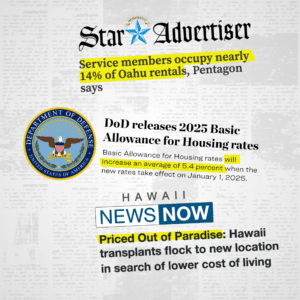

A January 2025 Pentagon report revealed that nearly 14% of Oʻahu’s private rental units are occupied by active-duty military personnel and their families—about 14,700 of 105,868 rentals—placing significant pressure on an already tight market. About 40% of all service people in Hawai‘i rent housing off base. Local officials, including Congressional Representatives Jill Tokuda and Ed Case, have emphasized that military competition in the rental market contributes to rising prices, especially when combined with trends like proliferating vacation rentals.

In addition, another 2,150 military personnel own homes on Oʻahu, further reducing the housing supply available to local families and driving up prices.

This issue is compounded by military benefits like rental housing allowances and VA loans, which give service members a competitive edge in the housing market, making it even harder for local residents to afford homes.

As a result, many longtime ‘ohana are priced out of their own communities and forced to leave. In 2023 alone, approximately 58,000 people moved from Hawaiʻi to the continental U.S.

This is how militarism shapes not only geopolitics but daily life, pressuring families out of their ancestral homes while securing comfort for those tasked with maintaining empire. And when longtime families are displaced, it changes more than just the housing market. It alters the culture, the sense of community, and the lived values that make Hawaiʻi what it is. The very things people say they love about this place—its warmth, its connection, its aloha—are being permanently reshaped.

Land Seized, Culture and Community Uprooted

Beyond the strain Hawaiʻi faces from having to absorb the housing needs of military personnel living off-base, the greater impact lies in the military’s physical footprint: bases and training areas that occupy 5.6% of our islands—more, by percentage, than in any U.S. state. Much of this land remains under military occupation and includes Hawaiian trust lands seized through the U.S. military–aided illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Such lands stolen from the Hawaiian Kingdom were later transferred to the U.S. in the so-called annexation of Hawaiʻi to the U.S. in 1898, “so-called” because this “annexation” occurred through a domestic law of the U.S., a joint resolution of congress rather than a treaty between the U.S. and the Kingdom of Hawai‘i, which the U.S. Constitution requires for the acquisition of new territory.

In addition to ʻāina seized through the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the U.S. seized additional land through its powers of eminent domain that allow the government to grab lands for whatever it pleases. For example, over 3,800 acres set aside by Ke Aliʻi Pauahi to support Kamehameha Schools were taken by the U.S. military, including 44 acres in Waikīkī now being used for an exclusive hotel and recreation area for military personnel. An additional 134 acres in Heʻeia, Koʻolaupoko, and 3,630 acres in areas near Puʻuloa, ʻEwa were seized from Pauahi in the name of U.S. national defense and empire as well.

Poisoned Waters, Poisoned Trust

When the U.S. military poisons our waters, it doesn’t just contaminate ecosystems, it corrodes the trust that people have in their ability to live safely on ancestral lands. These toxic releases are not isolated technical failures; they are the predictable outcomes of a system that treats Hawaiʻi as expendable, a buffer zone for the protection of the “mainland.” Included below are but a small set of examples of military-sourced contamination.

Between 2014 and 2023, the Marine Corps facility at Mōkapu released tons of chemicals into the environment, including 35,155 pounds of copper, 60,624 pounds of ethylene glycol, 181,622 pounds of lead, and lesser amounts of ethylbenzene and naphthalene. The largest release was 759,608 pounds of nitrate compounds from sewage wastewater.

In November 2021, between 19,000 and 27,000 gallons of jet fuel leaked into one of Oʻahu’s primary aquifers from the Red Hill storage facility. Nearly 93,000 people were displaced or affected, with families reporting rashes, nausea, and long-term health concerns. In 2025, a federal court ordered the U.S. government to pay $680,000 to affected families. An ongoing lawsuit by the Honolulu Board of Water Supply against seeks $1.2 billion from the U.S. Navy who have refused to cover remediation costs for the spill.

The decades of fuel leaks and the catastrophic November 2021 fuel spill had serious consequences for Oʻahu’s water supply. The Honolulu Board of Water Supply (BWS) was forced to shut down three major wells, the Hālawa Shaft, along with the ‘Aiea and Hīhīmanu wells, which together provided about 20% of urban Honolulu’s water. The BWS did that as a precaution against fuel migrating through the aquifer shared with the military system. This removal of 10 million gallons per day from the island’s pumping capacity compelled BWS to ramp up alternative sources and implement water conservation strategies. Simultaneously, two of the Navy’s three water wells serving over 90,000 military and civilian personnel were taken offline due to confirmed fuel contamination, placing additional strain on emergency water reserves. The crisis not only strained physical water resources but also eroded public confidence in the integrity of Oʻahu’s supply systems.

In the wake of the fuel spill disaster, the Navy released 1,300 gallons of firefighting foam concentrate containing high levels of poisonous PFAS at the Pearl Harbor-Hickam base. PFAS, often called “forever chemicals,” don’t break down easily in the environment or the human body. Even low levels of exposure have been tightly linked to a wide range of serious health risks, including various forms of cancer. In 2023, five Hawaiʻi locations were among the top 20 new locations reported by the U.S. military as having unsafe levels of more than 10,000 parts per trillion (PPT).

PFAS contamination levels recorded in Hawaiʻi are staggering. The contaminant level at the Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam was recorded at 2,620,000 PPT, the Fleet and Industrial Supply Center Pearl Harbor at 190,000 PPT, and the Marine Corps Base Hawaii, Mōkapu at 190,000 PPT.

To put this in perspective, the current EPA safety limit for PFAS in drinking water is just 4 PPT. That means 2,620,000 PPT is 655,000 times higher than the current EPA limit of what’s considered safe in drinking water. The 190,000 PPT at the other sites are 47,500 times higher.

And as recently as March of 2025, the Marine Corps Base Hawaii at Kāneʻohe was issued a Notice of Violation and Order (NOVO) for “failing the Whole Effluent Toxicity (WET) test and failing to disclose the addition of sodium hypochlorite into the treatment process at the facility” that treats wastewater sent into the ocean. The WET test assesses the toxic impact of wastewater on aquatic life.

If the military is truly here to protect us, why does it treat our home as disposable? Why are our waters poisoned, our lands desecrated, our communities displaced? No protector should endanger the very life it claims to defend.

The term “mainland,” still used on airport signage and in common speech, reinforces the idea that Hawaiʻi is peripheral and subordinate—never the center, always the colony.

The military says it defends national security. But for decades, it endangered Oʻahu’s drinking water. What kind of security sacrifices clean water for the local communities it claims to defend ?National security starts with clean water.

We Live on an Island

It might seem reassuring that many of the most heavily contaminated areas are off-limits to the public, restricted to military personnel. But that sense of security is misleading. Contaminants—whether jet fuel, heavy metals, or PFAS—move with the rains and the tides, with the wind and the water. They do not recognize fences, especially on an island. What seeps into groundwater or leaches into soil inevitably makes its way into our fishing grounds, our food systems, and our bodies.

But the danger doesn’t stop at environmental exposure. There is a deeper cost to these boundaries—one measured not just in toxins, but in memory, access, and identity. Over time, we have been conditioned to see exclusion as normal. Conditioned to believe that we need permission, background checks, or military escorts to visit places our kūpuna once cultivated, protected, and depended on for the genuine security of Hawai‘i. Heiau, fishing grounds, surfing spots, burial caves—spaces that once nourished entire communities—are now behind gates, guarded by fences, or erased from our memories.

This normalization of exclusion is one of the quietest tragedies of militarization. The right to gather, to practice, to feed our families from the land and sea, is not a privilege granted by military authorities—it is a right rooted in Hawaiian Kingdom law, protected under Article XII, Section 7 of the Hawaiʻi State Constitution, but ignored by the U.S.

And yet today, many of us no longer question our absence from these spaces. Soon, there may be no more kūpuna left who remember what it was like to walk freely on those shores, tend those loʻi, or fish in those waters. What we have lost is not just land—it is the sense of who we are, and where we belong.

Engaging and Reclaiming Ea: A Vision Rooted in Us, Not the U.S.

We find ourselves in a time where not only are $1.00 U.S. military leases are up for renewal, we find ourselves in a season of deep remembering, a time when the voices of our kūpuna call to us in the quiet and the chaos, inviting us to remember who we are and reimagine where we’re going. Ea is not something handed down by institutions of power; it is something we breathe into life together from the ground up. It grows through practice—in our hearts, in our minds, in our hands. Across our pae ʻāina, the seeds have already been planted, from mahiʻai restoring loʻi to lawaiʻa rebuilding stocks, and ʻōpio reclaiming ʻōlelo. Communities are designing economies that regenerate rather than extract. These everyday acts are the foundational stones of liberation.

Kūpuna like Mōkapu, Pōhakuloa, Mākua, and Kapūkaki don’t only hold histories of harm, they carry the potential for healing.

The way forward is not only about kia‘i or kūʻe, it’s about kūkulu and kūlia, and most importantly kākou, too. When we believe together in something better, that belief becomes behavior, and those behaviors grow a movement. When that movement is rooted in aloha, it becomes unstoppable.

This is more than reclaiming ʻāina. It is reclaiming our imagination, casting off the constraints of systems that would prefer we forget our power, and making room for the futures we know are possible.

E ala mai a nā hoa aloha o ko Hawai‘i pae ‘āina. Ea mai.

Ea mai Hawai’i.

1 EA, a working articulation: (1) A mindset, process, and actions, rather than a destination; (2) The life and breath that come from healthy, integral relationships with kānaka and ‘āina; (3) The individual or collective agency to activate aloha ‘āina and raise the well-being of our ‘āina, ‘ohana, kaiāulu, lāhui, and honua; and (4) The capacity to exercise kuleana (authority and accountability), in decisions ranging from specific responsibilities to the broadest realms of sovereignty.

2 Militarism is an ideology or belief system that glorifies the military, promotes military values (like discipline, hierarchy, aggression, obedience), and supports the use of military force as a primary tool for achieving national goals. Militarism enables and justifies militarization. Hand in hand with militarism is that paired concept of militarization, a process through which non-military aspects of society become influenced, shaped, or controlled by military logic, practices, institutions, or technologies. Militarization is how militarism manifests in everyday life, especially in colonized or occupied places.

3 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is a standard economic measure used by governments and economists to estimate the total monetary value of all goods and services produced within a nation’s borders over a specific time period. It is often used to signal the “health” or “strength” of an economy. But GDP only reflects the values of empire—it counts military spending, resource extraction, and luxury development as signs of wealth, while ignoring the things we as a lāhui often hold most dear. GDP does not account for our aloha for ʻāina, our relationships of kuleana to one another, or the continuity of ʻike from kūpuna to moʻopuna. It does not recognize the waiwai of fertile ʻāina, clean wai, or communities nourished in body and wailua. By the standards of GDP, a poisoned aquifer may still be a prosperous economy—so long as dollars keep flowing.

“This occupation is not confined to military zones; it spills into every aspect of life—economy, housing, language, water, memory—redefining what we believe is possible, and who we believe we are. Militarism does not just operate at the level of policy and geopolitics—it dictates who gets to stay in our homeland, and who must leave.”

Explore more: waihona.net